What is a Flood Protection Landform?

Visitors meander the winding paths amongst the urban prairie in Corktown Common. (Photo credit Nicola Betts)

POSTED: SEPTEMBER 23, 2016 I INFRASTRUCTURE, DESIGN, INNOVATION, SUSTAINABILITY, PARKS AND PUBLIC SPACES

By: Meghan Hogan

We recently took a look back into our archives and rediscovered one of Toronto’s most loved public spaces along the waterfront: Corktown Common. In that blog post, we explored how Corktown Common came to be, its exceptional design, and how its landscape was influenced by the topography of the flood protection landform that sits beneath the surface. However, the post didn’t delve deeply into what exactly the flood protection landform is and why it is important. This time around, we’re rewinding to the beginning – before this award-winning park existed – and exploring this essential piece of urban infrastructure.

An aerial view of the West Don Lands prior to revitalization.

A quick history of the West Don Lands

Back in 2003, the neighbourhood we know today as the West Don Lands was nothing but an abandoned and derelict site. Previously home to a number of Toronto’s most prolific factories and warehouses, including a portion of the Gooderham & Worts Distillery and Enoch Turner’s Brewery, the area was a relic of Toronto’s industrial past. As these industries relocated throughout the 20th century, they left behind a large, vacant brownfield site that sat within the designated floodplain of the Don River.

This area has a long history of flooding dating back to the 1870’s through to modern day. Thanks to its unique location at the mouth of the Don River and the Keating Channel, the area was prone to severe flooding under extreme storm conditions, similar to what we saw with Hurricane Hazel in 1954. Under these conditions, rainfall and stormwater run-off along the Don River watershed could cause water levels to exceed river bed limits and spill into the neighbouring areas.

Hurricane Hazel had devastating effects on Toronto, including 81 deaths, and washed out bridges, streets and homes. (Image via City of Toronto Archives)

Fast forward to 2003 and Waterfront Toronto was charged with overseeing the revitalization of the West Don Lands. But before any development could occur, the necessary steps to flood protect the area had to be taken. To begin, Waterfront Toronto and Toronto Region Conservation Authority undertook a Class Environmental Assessment to better understand the site conditions and develop a plan to remove the flood risk. Constructing a large “berm” (although technically not a berm, but that’s an argument for another day) was identified as the best option to flood protect the area and unlock its full potential.

Mounds of soil blanket the West Don Lands in order to squeeze out groundwater.

Before construction could begin, engineers had to address the sites unstable ground conditions. You see, prior to the straightening of the lower Don River in 1892, its original course used to meander through the West Don Lands. This meant that the site now rested on top of an underground layer of soggy peat that engineers knew would surely shift and settle under the weight of the “berm”. So they undertook an interesting process called surcharging, whereby they piled tons (literally tons and tons) of dirt on top of the site and effectively squeezed the water out of the ground. Once the water was removed, they were ready to begin construction.

Flood Protection Landform Composition

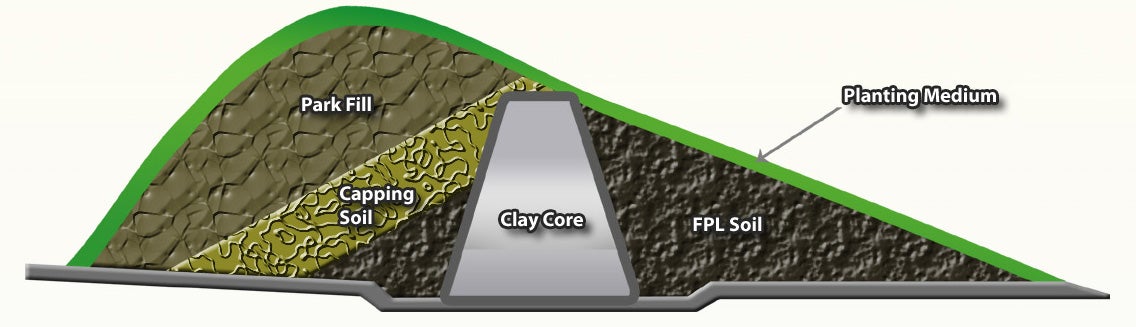

Extending from Queen Street in the north to the railway tracks in the south, the flood protection landform is 775 metres long, 4 metres high and is made of roughly 400,000 cubic metres of clean soil from across the Greater Toronto Area. Running like a ribbon through its centre is a 1.5 metre deep clay core, which varies in height to prevent water from penetrating through it. It also includes an amoured slope, comprised of varying sizes of stone that help prevent the clay core from eroding and protect against the Don River’s rapid waters.

A sample cross section of the flood protection landform.

As we mentioned in our previous blog post, Corktown Common features three distinct landscapes: the wet side (or urban prairie), the dry side (or western portion), and the northern entrance. The wet side and dry side both feature gentle slopes that meet in the middle, known as the crest. In the event of a storm, the wet side would quite literally get wet as it holds off floodwaters, effectively keeping the dry side dry. Each of these three landscapes also incorporates distinct elements of flood protection and stormwater management.

We call the eastern edge of the park running parallel to the Don River the urban prairie or “wet side.” It features a gentle slope and walking paths that lead visitors to the Bala Underpass and connects to the Lower Don River trail network and the river beyond. You won’t find any woody vegetation (trees, shrubs, etc.) or structures here since the roots and substructures could potentially dislodge and uproot the armoured stone or clay core beneath during a flood event and compromise the landform’s ability to hold back the flood waters. Instead, it features long prairie grass that beautifies the area, and also helps prevent any erosion of the slope.

Top image: The open lawns at Corktown Common are perfect for recreational activities. Above: The extensive marsh is an integral element of the park’s stormwater management system. (Photo credit: Nicola Betts)

The “dry side” of the park features a dynamic landscape that is shaped by the flood protection landform, unfolding from the crest of the landform into open lawns and knolls that create flexible spaces that can accommodate a variety of recreational activities. While this section of the park does not include flood protection measures, it does feature an extensive marsh (1,300 square metres) that connects with the park’s stormwater management system, receiving and treating storm water runoff from the flood protection landform.

Lastly, is the northern entrance to Corktown Common. Once visitors past beneath the merged King and Queen Street bridge, they will experience a landscape similar to the previously described “wet side”. This is also a critical portion of the flood protection landform and similarly features long prairie grass.

An aerial view of Corktown Common and its unique landscapes that are defined by the flood protection landform. (Image via American Society of Landscape Architects)

An aerial view of Corktown Common and its unique landscapes that are defined by the flood protection landform. (Image via American Society of Landscape Architects)

Construction of the flood protection landform was completed in 2012 by Infrastructure Ontario. Not only did its completion make possible the development of the West Don Lands and Corktown Common, but its effects extend well beyond the neighbourhood. More than 500 acres of prime downtown lands, including the Financial District, are now protected from flooding and it is estimated that the flood protection landform has removed the risk of more than of $160 million in flood damages in the event of a major storm (does the storm of 2013 ring a bell?).

This map highlights the 500 acres of land that the flood protection landform currently protects. It also shows future flood protection areas, including the Port Lands and adjacent areas that are currently not flood protected.

In the face of rising climate change and its challenging effects, the flood protection landform is an excellent example of how urban cities like Toronto can future-proof itself in a compelling and practical way.